Funtran - Maths to the Rescue

2024-09-13

Last weekend I took on snakeCTF 2024 Quals. As I’m still focused on improving my binary skills, I decided to go for a reverse engineering challenge called Funtran. It certainly kept me busy for some hours and reminded me that paying attention in maths every now and then was worth it. :)

TL;DR

Funtran is a reverse engineering challenge where the objective is to provide a valid flag to the given program by analyzing its verification mechanism. The challenge can be solved by exctracting the relevant parts of the binary and formulating a mathematical problem. This problem can then be solved using tools such as SciPy or z3.

The Challenge

As a starting point a file called chall is provided. When executed it prompts for a flag and outputs whether the entered flag was correct. So the program seems to take user input, verifies it presumably by doing some calculations on it and then outputs the result. If we know how the verification works it should be possible to guess or calculate the expected flag.

$ ./chall

Enter the flag:

snakeCTF{fLaG}

Wrong flag

Some basic enum reveals that the binary was likely compiled with GNU Fortran and coded in Fortran.

$ checksec --file=chall

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Full RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: PIE enabled

$ ldd chall

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007ffe1e9df000)

libgfortran.so.5 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libgfortran.so.5 (0x00007fd205c00000)

libm.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libm.so.6 (0x00007fd205f3f000)

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007fd205a1b000)

libgcc_s.so.1 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libgcc_s.so.1 (0x00007fd205f12000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007fd20603e000)

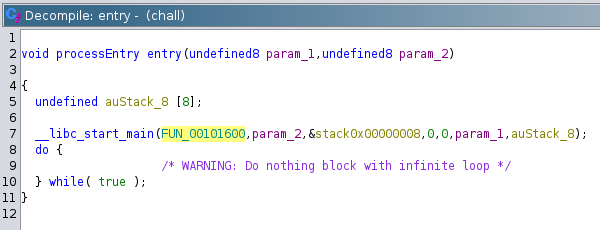

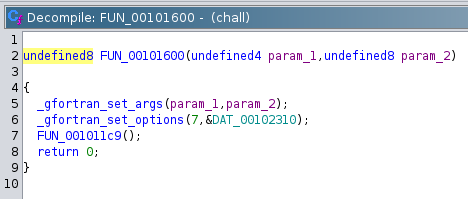

Let’s have a look at the decompiled program. In Ghidra we first have to jump through a couple of hoops until we end up in the function where most of the logic resides.

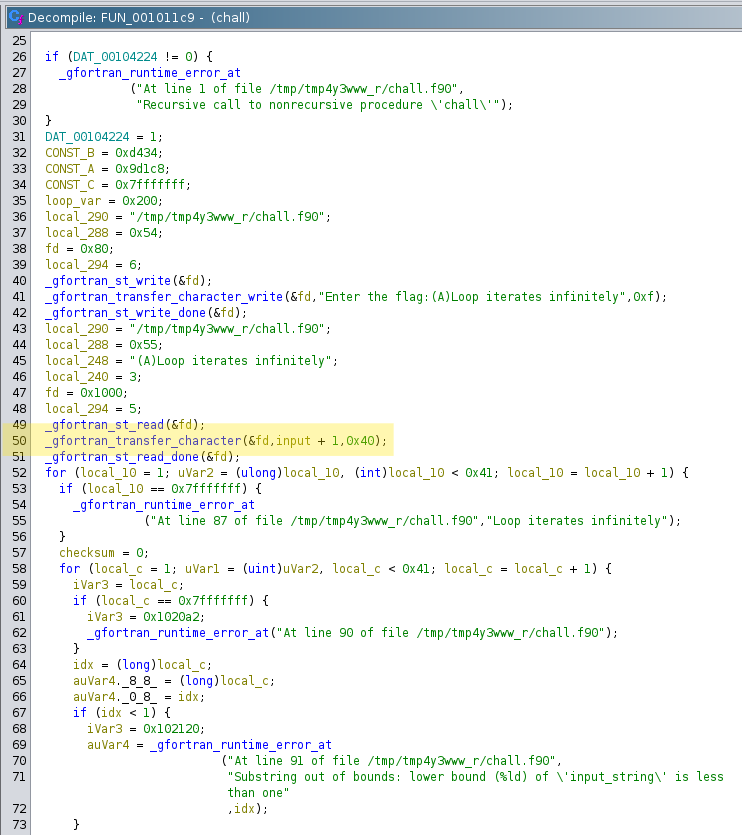

In the function shown below, let’s call it main, we first have to filter out the relevant parts. There are lots of error conditions that obfuscate the program logic or at least make it harder to understand. The call to _gfortran_transfer_character presumably reads our input into a buffer which I named input. This buffer is defined at the very beginning of the function and has a length of 74 bytes. So user input is read, what happens next?

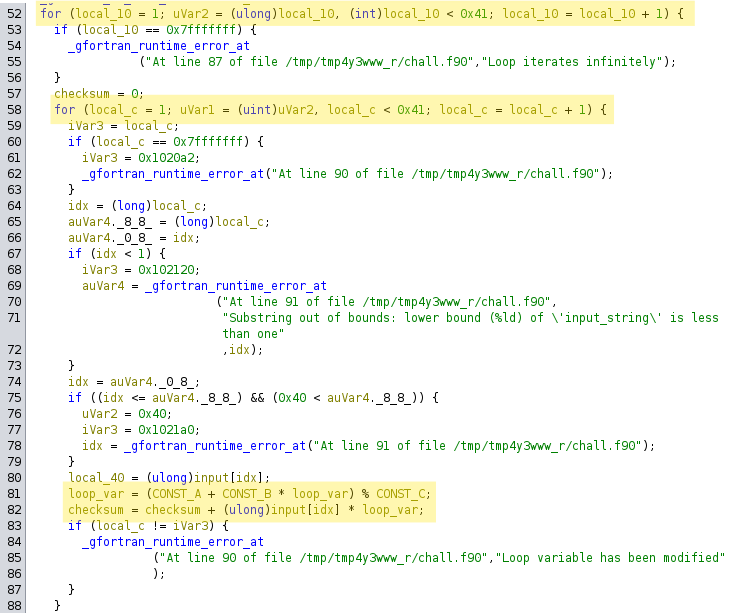

Further down in the decompiled program we discover two nested for loops. Inside the inner loop we can see that some kind of checksum value is calculated using constant values, one variable that is altered within that loop (loop_var) and the input buffer.

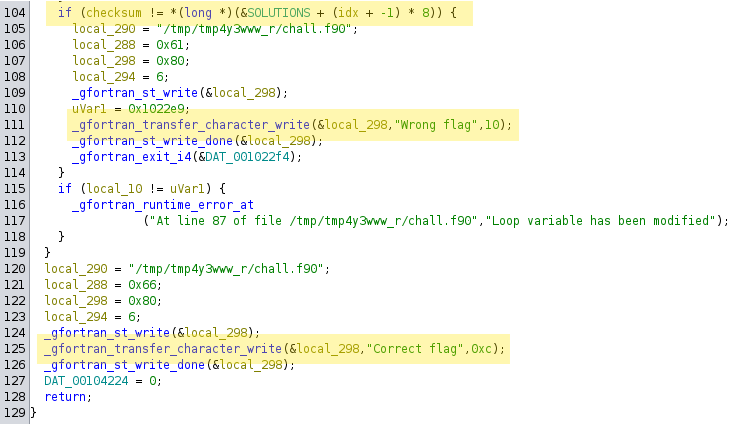

At the end of the function that checksum is verified against a static value that is defined within the binary’s data section. The offset calculation tells us that this SOLUTIONS reference holds an array of longs with a length of 8 bytes each since we’re always jumping idx * 8. This if is also where the two cases, successful validation and failing validation take different code paths. So at here we obviously want to pass that check to end up in the Correct flag case.

Some Theory

To analyze this logic further we can represent it as pseudo code so we can focus on the relevant parts only. Without all the error handling and bounds checking the flow looks fairly simple.

CONST_A = 0x9d1c8

CONST_B = 0xd434

CONST_C = 0x7fffffff

loop_var = 0x200

input = stdin()

FOR 1 -> 64 -> i

checksum = 0

FOR 1 -> 64 -> j

loop_var = (CONST_A + CONST_B * loop_var) % CONST_C

checksum = checksum + input[j] * loop_var

IF checksum != SOLUTIONS[i - 1]

FAIL

SUCCESS

The inner loop calculates a checksum over input[] that is compared to the static SOLUTIONS array at the end of each iteration of the outer loop. We can calculate the value of loop_var for every iteration but since we only know the desired value for checksum at the end of every inner loop we can’t simply reverse its logic. We wouldn’t be able to calculate the individual values of input[].

In an attempt to understand this problem better we can unroll the loop and write down what happens in every iteration of the inner loop.

01 01 checksum = 0 + input[0] * loop_var[0][0]

01 02 checksum = (input[0] * loop_var[0][0]) + input[1] * loop_var[0][1]

01 03 checksum = ((input[0] * loop_var[0][0]) + input[1] * loop_var[0][1]) + input[2] * loop[0][2]

01 04 checksum = (((input[0] * loop_var[0][0]) + input[1] * loop_var[0][1]) + input[2] * loop[0][2]) + input[3] * loop_var[0][3]

We can quickly see that checksum forms an equation with several unknowns. Moreover if we take the outer loop into consideration it becomes evident that the program flow represents a system of equations. We could write it like this:

Y1 = a11 * x + a12 * y + a13 * z + ...

Y2 = a21 * x + a22 * y + a23 * z + ...

Y3 = a31 * x + a32 * y + a33 * z + ...

...

In this representation the following applies:

Ynequalschecksum[n]equalsSOLUTIONS[n]-> knowna[i][j]equals the pre-calculated value ofloop_varfor every iteration (i = idx outer loop, j = idx inner loop) -> knownx, y, y, ...equalsinput[n]-> unknown

So in theory, all we have to do is to solve a system of equations with 64 equations and 64 unknowns.

Cracking the Challenge

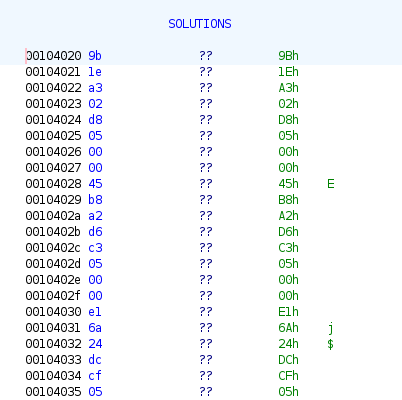

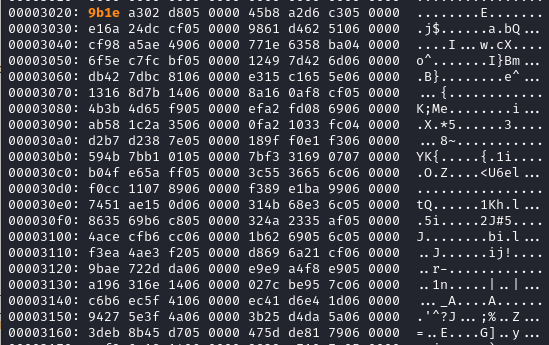

Let’s write some code that solves this problem for us. We can start by extracting the SOLUTIONS array from the challenge binary. As of now we know that it should contain 64 long values with a size of 8 bytes each which makes 512 bytes in total.

We can grab the correct offset using xxd.

To extract relevant part from the binary we use dd with an offset of 0x3020 as shown above.

dd if=chall of=exctracted.bin bs=1 skip=$((0x3020)) count=512

Since my first attempts of solving this problem using z3 failed I resorted back to using plain maths and SciPy. As discussed in the theory part we have three kinds of values which we have to turn into matrices or vectors respectively. We have a coefficient matrix A (pre-calculated values of loop_var), a result vector B (values from static SOLUTIONS array) and a vector c containing the results if any are found. At the end we would expect vector c to contain numbers that represent ASCII characters. So we have to make sure that only non-floating point solutions are considered.

The code works as follows. First the SOLUTIONS values are read from extracted.bin to later populate result matrix B. Then we pre-calculate the loop_var values which are stored in the coefficient matrix A. We define another vector c where the solution of our problem will be stored and finally we let SciPy do its magic.

import numpy as np

from scipy.optimize import linprog

import struct

# read exctracted binary data

extr = open("exctracted.bin","rb").read()

DATA = []

for i in range(0, 64):

# unpack 8-byte longs, little-endian

num = struct.unpack('<q', extr[i*8:i*8+8])[0]

DATA.append(num)

CONST_A = 0x9d1c8

CONST_B = 0xd434

CONST_C = 0x7fffffff

def calc_coefficients():

coeffs = [[0]*64 for i in range(64)]

loop_var = 0x200

for i in range(64):

for j in range(64):

loop_var = (CONST_A + CONST_B * loop_var) % CONST_C

coeffs[i][j] = loop_var

return coeffs

# coefficient matrix

A = np.array(calc_coefficients())

# result matrix

B = np.array(DATA)

# make sure only non-floating point solutions are considered

c = np.zeros(A.shape[1])

res = linprog(c, A_eq=A, b_eq=B, method="highs")

print("".join(chr(int(round(res.x[i]))) for i in range(64)))

If we execute this script we can observe that a solution is found.

$ python solve.py

snakeCTF{Funs_in_funtran_are_fun_or_funny_funs_5a6013bf9cda513e}

$ ./chall

Enter the flag:

snakeCTF{Funs_in_funtran_are_fun_or_funny_funs_5a6013bf9cda513e}

Correct flag

That’s it!

Another Attempt Using z3

Obviously the same can be achieved using z3. The issue with my initial attempts was that I was using Python’s built-in sum function instead of the Sum function provided by z3.

import struct

from z3 import *

set_param('verbose', 10)

#set_param('trace', True)

# read exctracted binary data

extr = open("exctracted.bin","rb").read()

DATA = []

for i in range(0, 64):

# unpack 8-byte longs, little-endian

num = struct.unpack('<q', extr[i*8:i*8+8])[0]

DATA.append(num)

CONST_A = 0x9d1c8

CONST_B = 0xd434

CONST_C = 0x7fffffff

def calc_coefficients():

coeffs = [[0]*64 for i in range(64)]

loop_var = 0x200

for i in range(64):

for j in range(64):

loop_var = (CONST_A + CONST_B * loop_var) % CONST_C

coeffs[i][j] = loop_var

return coeffs

c = [Int(f'input_{i}') for i in range(64)]

A = calc_coefficients()

B = DATA

solver = Solver()

for i in range(64):

equation = Sum([A[i][j] * c[j] for j in range(64)])

solver.add(equation == B[i])

if solver.check() == sat:

model = solver.model()

print("".join(chr(model[c[i]].as_long()) for i in range(64)))

else:

print("no solution")

$ python solve2.py

snakeCTF{Funs_in_funtran_are_fun_or_funny_funs_5a6013bf9cda513e}

Resources

- SciPy Scientific Computing in Python - https://scipy.org/

- z3 Theorem Prover - https://github.com/Z3Prover/z3